A 70-year old female presents to the ED for evaluation of left hip pain after a mechanical fall. X-ray shows a nondisplaced femoral neck fracture. After bedside evaluation, the Orthopedic team would like to plan for surgical correction with open reduction internal fixation (ORIF). Her past medical history is significant for CAD s/p 3-vessel CABG 4 years ago, HFrEF (EF 25-30%), IDDM, CKD, COPD (on 2L home oxygen), OSA. Prior to the fall she was at her baseline state of health without any recent chest pains or new dyspnea. Given her multiple comorbidities, the Orthopedic team is requesting “clearance” prior to taking her to the OR tomorrow morning.

Considering the patient’s multiple comorbid symptoms, how do you proceed in conducting this ‘pre-op’ eval? Pre-op labs? 2D Echo? Cardiology Consultation? Stress test? Pulmonary consultation?

Keep in mind, the bulk of this post is targeted towards inpatient evaluation of patients.

Can a patient ever be risk-free from surgery?

No. Obviously no. Therefore, avoid the phrase “cleared for surgery” as no patient is without risk despite the type of surgery or absence of co-morbid conditions. Rather, it is our job to medically optimize, consider additional testing to quantify known/unknown co-morbid conditions, and risk stratify the patient prior to the surgical procedure.

Use more appropriate phrases such as “Patient is at intermediate risk for intermediate risk surgery, is medically optimized with stable co-morbid conditions with no further testing necessary and may proceed with surgery.” Additionally, feel free to include in your documentation and discuss with your surgical colleagues and patients the percentages provided from the information below.

What is the risk of the surgery?

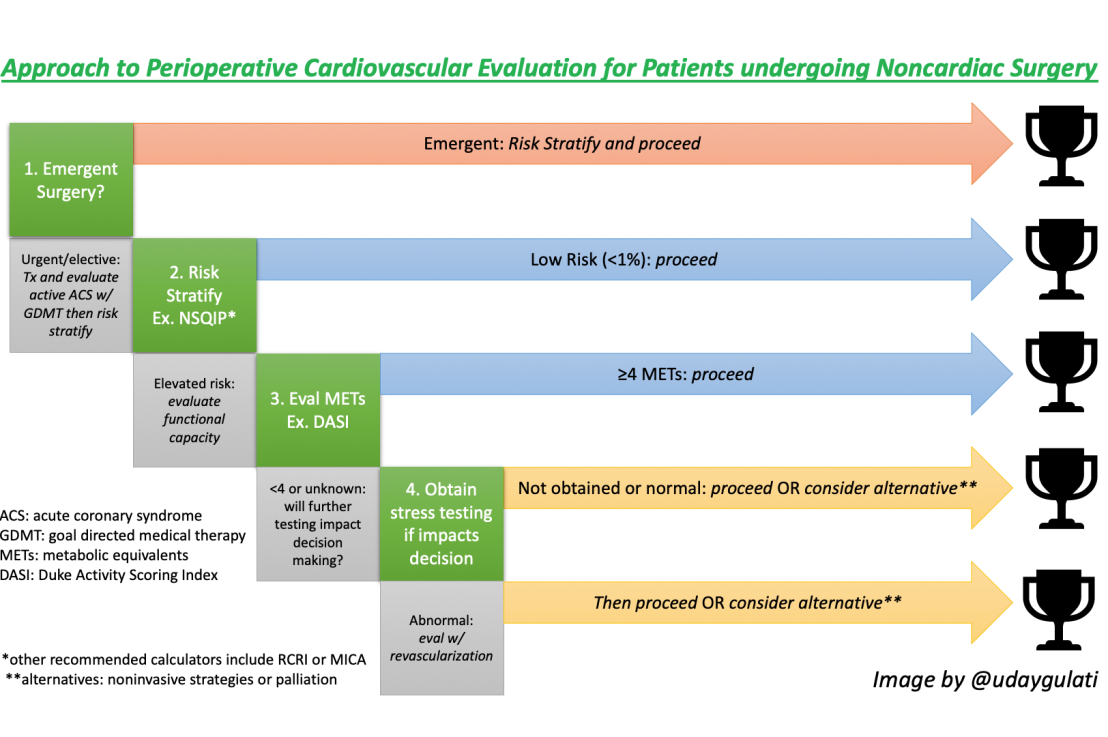

Prior to starting the pre-operative evaluation, one should consider the necessity of surgery. Certainly, emergent cases forgo the need for any pre-operative testing, however urgent surgery may need to be put on hold until the patient is medically optimized for the procedure . Lastly, goals of care should always be discussed with patient as to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Consider the type of surgery which carry their own risks for cardiovascular death and MI within the next 30-days.

In simpler terms, read:

| Vascular – larger vessel Cardiopulmonary GI – emergent Adrenals | High Risk |

| Vascular – peripheral, endovascular repair Head/neck Nephrological / Urological Hip, spine – majority | Intermediate Risk |

| Superficial Eyes Dental Orthopedic – minor | Low Risk |

What about risk calculators?

Risk calculators are helpful in providing an approximate percentile risk for primarily Major Adverse Cardiac Events (MACE) ie cardiovascular and pulmonary complications by evaluating comorbid conditions (HTN, HF, COPD, etc.) with the type of surgery. These numbers can be useful for both providers and patients to assess benefit vs risk and consider additional testing for further risk stratification.

There are multiple risk calculators out there, among which the most popular are:

- Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI)

- Myocardial Infarction or Cardiac Arrest (MICA/Gupta) and

- American College of Surgery – National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP)

Each provides a different extent of risk stratification. Which one should you use?

These three are quite different and can provide quite different risk assessments. Without diving into too much detail, each study has been validated differently and may apply to different populations.

- In a study published in 2018 in the American Journal of Cardiology1, a comparison of 4 risk calculators were studied in predicting postoperative cardiac complications after noncardiac operations which showed similar predictive value in low risk patients however the MICA was more predictive of events in higher risk patients.

Based on this author’s literature review, a simple recommendation could be:

| Quick and easy | RCRI |

| Most detailed recommendations and procedure specific | ACS-NSQIP |

| Best for higher risk patients | MICA (GUPTA) |

| Not recommended | other calculators |

How to evaluate those with higher risk?

Not all those with >1% risk based on the above calculators need additional testing. Instead, further minimize the need for unnecessary stress testing or even revascularization (these are not risk-free) by evaluating functional capacity prior to surgery.

The ACC recommends using the Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) to estimate a patient’s active metabolic equivalents (METs).

Those with greater capacity do not need additional testing (≥4) vs those with poor capacity or those who you are unable to assess should have considerations for additional testing.

Who needs further preoperative stress testing?

This is usually pharmacological stress testing. After all, the subjective assessment of METs usually correlates with results of exercise stress testing.

No: Any low risk patients. High risk patients with good exercise capacity (METS ≥ 4)

Yes: Patients undergoing major vascular surgery. Increased risk patients with unknown or poor functional status ONLY if management would change.

What about preoperative revascularization?

For the most part, no. While there used to be the thinking that aggressive treatment of coronary artery disease before surgery may improve outcomes, the CARP trial provided pretty convincing evidence to the contrary in patients with stable CAD who are scheduled for elective vascular surgery: preoperative revascularization has NOT shown to improve mortality.7 As a follow up, the DECREASE-V Pilot Study even showed that in patients with cardiac high-risk patients underoing vascular surgery, ie an abnormal stress echocardiography, preop revascularization has NOT shown to decrease rates of postoperative MI/death at 30 days or 1 year.8

Keep in mind, possibly due to the need for further evidence, the ACC/AHA guidelines do still recommend that in clinicians who pursued stress testing and received abnormal results, coronary angiography and revascularization may be considered, according to usual clinical practice guidelines and on the extent of the abnormal test.

What pre-op tests should you obtain?

By this time, the patient has likely had routine blood work testing in the ED that likely includes CBC, BMP, Coags, Type/Screen. If the procedure is elective and labs have not already been ordered, consider obtaining certain labs for the following indications. Your job is to help corroborate this data with known and unknown co-morbid conditions. As general takeaways of the literature and input from expert opinion, consider:

| Hemoglobin | anticipated major blood loss has symptoms of anemia |

| WBC | Sx suggesting infection or myeloproliferation takes myelotoxic medications |

| Platelets | Hx bleeding diathesis or myeloproliferative disorder takes myelotoxic medications |

| Coags | Hx bleeding diathesis, liver disease, malnutrition or liver disease on heparin, warfarin, antibiotics or other CYP450 altering meds |

| Electrolytes | known renal insufficiency, CHF takes meds that alters electrolytes |

| BUN, Cr | Hx CKD, HTN, DM, CAD major surgery takes meds that alters renal function |

| Glucose | Hx DM, obesity |

| LFTs | Hx cirrhosis |

| UA | Sx suggesting UTI instrumentation of GU tract |

| ECG | Hx CAD, DM, uncontrolled HTN, CKD |

| CXR | Sx suggesting active pulmonary disease |

| BNP | Age ≥ 65 + RCRI > 1 OR Age 45-64 with Hx of significant CVD (consider also obtaining post-op) |

| Troponin | absolutely: High risk patients (RCRI ≥ 1) or Age ≥65 with known atherosclerotic disease (consider 6-12 hours prior to surgery and post op days 1 to 3) maybe: no known CVD but + risk factors (smoking, HTN, HLD) |

| EKG | absolutely: Sx of angina (or equivalent), risk factors + intermediate/high risk surgery maybe: Asx CAD Hx arrhythmia, PAD, structural heart disease low/intermediate risk surgery (consider also obtaining post-op) |

| 2D Echo | unexpected dyspnea Hx HF w/o recent 2D echo or change in condition suspected valvular disease or Hx valve disease w/ no echo in last year |

What about risk stratifying pulmonary complications?

A good history and physical examination is the most important tool in determining postoperative pulmonary risk. Besides evaluating the patient’s pulmonary history, pay special attention to the lung examination, oxygen saturation, serum bicarbonate level, etc.

Pulmonary Risk Calculators

Much like the cardiac risk calculators, there are four available scoring systems.

ARISCAT Score is a scoring system that helps estimate post-operative pulmonary complications of any severity and is the most used.

Arozullah Respiratory Failure Index – very complicated and mostly used in research settings.

Gupta Calculator for Postoperative Respiratory Failure – Predicts the risk of ventilation > 48 hours or reintubation within 30 days.

Gupta Calculator for Postoperative Pneumonia – Predicts the risk for pneumonia after surgery

Pulmonary Testing

PFTs – Required in lung resection however generally not necessary in the acute setting

ABG – Current data do not support the use of preoperative ABG.

CXR – Reasonable to obtain if have suspicion for intrathoracic pathology OR in patients age >50 undergoing high-risk surgery with no CXR within the past 6 months.

In Summary…

- Preoperative testing should be dictated by the patient’s clinical condition and abnormal findings on history and exam.

- It is important to consider the inherent risk of the surgery alone in conjunction with the patient’s personal risk given co-morbid conditions.

- Use above risk calculators to help predict postoperative complications to help guide additional testing.

- Consider the following generalized approach to guide preoperative evaluation:

- Avoid using terms such as “cleared for surgery” in your documentation. Use more appropriate phrases such as “Patient is at intermediate risk for intermediate risk surgery, is medically optimized with stable co-morbid conditions with no further testing necessary and may proceed with surgery.” Additionally, feel free to include in your documentation and discuss with your surgical colleagues and patients the percentages provided from these calculators.

References:

1 Cohn, S. L., & Fernandez Ros, N. (2018). Comparison of 4 Cardiac Risk Calculators in Predicting Postoperative Cardiac Complications After Noncardiac Operations. The American Journal of Cardiology, 121(1), 125–130.

2 Duceppe, E., et al, (2017). Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Management for Patients Who Undergo Noncardiac Surgery. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 33, 17–32.

3 Devereaux, P., PeriOperative Ischemic Evaluation) (POISE) Investigators. (2011). Characteristics and short-term prognosis of perioperative myocardial infarction in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 154(8): 523.

4 Choosing Wisely Campaign. American College of Physicians

5 Lee, A., et al, (2014). 2014 ACC/AHA Guideline on Perioperatie Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Vol 64, Issue 22.

6 Cohn, S. L. (2016). Preoperative Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery. In the Clinc, Annals of Internal Medicine.

7 McFalls, E., et. al, (2004). Coronary Artery Revascularization Prophylaxis (CARP). Coronary-Artery Revascularization before Elective Major Vascular Surgery.NEJM. 351(27):2795-2904.

8 Poldermans, D., DECREASE Study Group. (2007). A clinical randomized trial to evaluate the safety of a noninvasive approach in high-risk patients undergoing major vascular surgery: the DECREASE-V Pilot Study. Journal of American College of Cardiology. 49 (17): 1763-9.

9The Curbsiders Episode #135 Perioperative Medicine: Assess & Optimize Risk.

Post reviewed and edited by @udaygulati